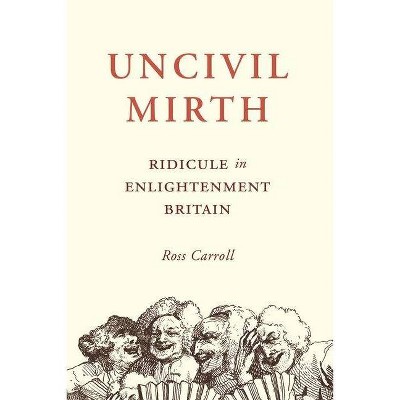

Uncivil Mirth - by Ross Carroll (Hardcover)

Similar Products

Products of same category from the store

AllProduct info

<p/><br></br><p><b> About the Book </b></p></br></br>"Ridicule is a ubiquitous feature of modern politics. Few participants in a political contest can resist the temptation to ridicule their opponents in order to demean them, persuade others to regard them with scorn, or expose their hypocrisy. Yet ridicule also has the potential to undermine the conditions necessary for politics itself, converting disputants into belligerents and debate into the silence of mutual disdain. Unsurprisingly, then, ridicule has not only been common in political debate but has often been at the centre of such debate as well. In contemporary debate, some commentators worry that citizens are reaching for ridicule and contemptuous dismissal at the expense of more earnest forms of political engagement. Theorists of deliberative democracy have warned that there might be something inherently uncivil, trivializing, or morally objectionable about the use of ridicule in political debate. Others are more inclined to accept that a society characterized by vibrant political contestation will not lack for ridiculers deriding, shaming, and insulting each other. They counsel that ridicule is more urgent, and necessary, now than ever, particularly as a weapon against authoritarian personalities who are least able to tolerate it. This book brings some much-needed historical contextualization to this debate by revisiting a moment in which the place of ridicule in politics was subjected to more intense theoretical scrutiny than any other: eighteenth-century Britain. The relaxing of censorship and deregulation of the printing trade in the 1690s led to an explosion of political and religious satires, many of which were mobilized in the political contest over the recently passed Toleration Act. This new vogue for ridicule led numerous critics to warn that indulging in it excessively could disfigure one's character, undermine religion, and sow civil discord. But ridicule also had vocal defenders, none more influential than the Third Earl of Shaftesbury. Far from merely accepting ridicule as the unfortunate by-product of free public debate, Shaftesbury defended the "trial of ridicule" as a useful method for exposing the conceitedness of fanatics and overly zealous clerics, the two groups most threatening to toleration. From David Hume to Mary Wollstonecraft, Carroll traces Shaftesbury's impact, examining how the Earl's many followers and critics throughout the eighteenth century responded to the challenge of using ridicule responsibly in political and religious controversy"--<p/><br></br><p><b> Book Synopsis </b></p></br></br><p><b>How the philosophers and polemicists of eighteenth-century Britain used ridicule in the service of religious toleration, abolition, and political justice</b> <p/>The relaxing of censorship in Britain at the turn of the eighteenth century led to an explosion of satires, caricatures, and comic hoaxes. This new vogue for ridicule unleashed moral panic and prompted warnings that it would corrupt public debate. But ridicule also had vocal defenders who saw it as a means to expose hypocrisy, unsettle the arrogant, and deflate the powerful. <i>Uncivil Mirth</i> examines how leading thinkers of the period searched for a humane form of ridicule, one that served the causes of religious toleration, the abolition of the slave trade, and the dismantling of patriarchal power. <p/>Ross Carroll brings to life a tumultuous age in which the place of ridicule in public life was subjected to unparalleled scrutiny. He shows how the Third Earl of Shaftesbury, far from accepting ridicule as an unfortunate byproduct of free public debate, refashioned it into a check on pretension and authority. Drawing on philosophical treatises, political pamphlets, and conduct manuals of the time, Carroll examines how David Hume, Mary Wollstonecraft, and others who came after Shaftesbury debated the value of ridicule in the fight against intolerance, fanaticism, and hubris. <p/>Casting Enlightenment Britain in an entirely new light, <i>Uncivil Mirth</i> demonstrates how the Age of Reason was also an Age of Ridicule, and speaks to our current anxieties about the lack of civility in public debate.</p><p/><br></br><p><b> Review Quotes </b></p></br></br><br>Witty and insightful. . . . this study could hardly be more timely.<b>---Jan Machielsen, <i>Times Literary Supplement </i></b><br><br>For those curious to know the role of ridicule in eighteenth-century Britain, Ross Carroll's <i>Uncivil Mirth</i> is the place to start. In it, readers will find a reliable survey of the main lines of argument about ridicule's function in enlightened public debate.<b>---Mark G. Spencer, <i>LSE Review of Books</i></b><br><p/><br></br><p><b> About the Author </b></p></br></br><b>Ross Carroll</b> is senior lecturer in political theory and a member of the Centre for Political Thought at the University of Exeter. Twitter @rossecarroll

Price History

Price Archive shows prices from various stores, lets you see history and find the cheapest. There is no actual sale on the website. For all support, inquiry and suggestion messagescommunication@pricearchive.us